The Mississippi River is one of the most engineered rivers in the world. Nowadays, as a “working river”, it carries grain, coal, and goods that power regional and national economies. At the same time, our Mighty Mississippi provides vital habitat for hundreds of fish and wildlife species, supports healthy ecosystems such as floodplain forests and wetlands, and sustains communities and millions of people.

As a nation, we have focused on commercial navigation and flood control for 200 years, and only in recent decades have we asked, can we support commercial navigation and flood risk reduction without sacrificing the health of the River - and all who rely on it?

The Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program—better known as NESP—is one of the federal government's attempts to answer that question. Today, as climate change, biodiversity loss, and aging infrastructure put new pressures on the River, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ NESP program may be more important than ever.

How We Got Here: Engineering a River

More than 200 years ago, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began clearing snags and shaping the Mississippi River for commerce. In the early 20th century, the Upper Mississippi River was transformed by a system of locks and dams and other engineering techniques designed to support commercial navigation. These structures created a reliable navigation channel, but they also reshaped the River’s natural flow, sediment transport, floodplain connectivity, and habitat.

By the mid-20th century, river commerce was booming nationwide. On the Mississippi, plans to expand navigation and capacity accelerated, while environmental impacts mounted. Scientists, communities, and environmental advocates began raising alarms about declining habitat, shrinking backwaters, and stressed fish and wildlife populations. Ultimately, those concerns led Congress to authorize the Upper Missisippi River Restoration Program (UMRR) in 1986—a landmark effort to improve ecological monitoring and rehabilitation.

Why NESP Was Created

By the early 2000s, pressure was growing to expand lock capacity to improve commercial navigation efficiency. At the same time, environmental advocates were clear: any new navigation investment had to come with real commitments to ecosystem restoration.

NESP emerged as a compromise that navigation improvements and habitat restoration would proceed together. If, as a nation, we were going to modernize infrastructure, we would also invest in the Mississippi River’s long-term ecological health.

At least, that was the idea.

After NESP was authorized in 2007, the program struggled to get off the ground. Federal reviews raised concerns about the economic justification for the new locks, and funding stalled when Congress eliminated earmarks. For more than a decade, NESP existed mostly on paper—authorized, but unfunded.

From Lock and Dam 26 to NESP — Advocacy Changes the River

In the 1950s and 1960s, Mississippi River commerce was expected to grow indefinitely, and navigation expansion moved quickly. In 1969, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers finalized plans to replace Lock and Dam 26 near St. Louis, just months before the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) became law.

Environmental advocates sued to require the project to comply with NEPA and won, forcing the Corps to consider the project’s environmental impacts. Continued advocacy led Congress to authorize the Great River Environmental Action Teams in 1976, and, later, the Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program in 1986.

When Lock and Dam 26 was replaced in 1989 by Mel Price Locks and Dam, its dual 600- and 1,200-foot locks symbolized the growing tension between navigation efficiency and ecosystem protection.

The tension ultimately gave rise to the Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program (NESP)—a commitment that navigation and restoration would proceed together.

NESP Restarts, but Gaps Persist

Momentum returned in the early 2020s. New federal investments and the return of congressional-directed spending (formerly called “earmarks”) helped advance some components of NESP. Navigation projects are moving ahead. Fish passage is improving connectivity for aquatic species. And ecosystem planning is underway.

But major gaps remain.

One of the most significant is systemic mitigation—a required effort to address the cumulative environmental impacts of expanding navigation capacity across the River system. While Congress approved funding for this work, there is still no comprehensive plan in place.

At the same time, ecosystem investments have not kept pace with navigation spending, falling short of the balance originally promised.

NESP Reach Planning: Developing the Next Generation of Habitat Projects

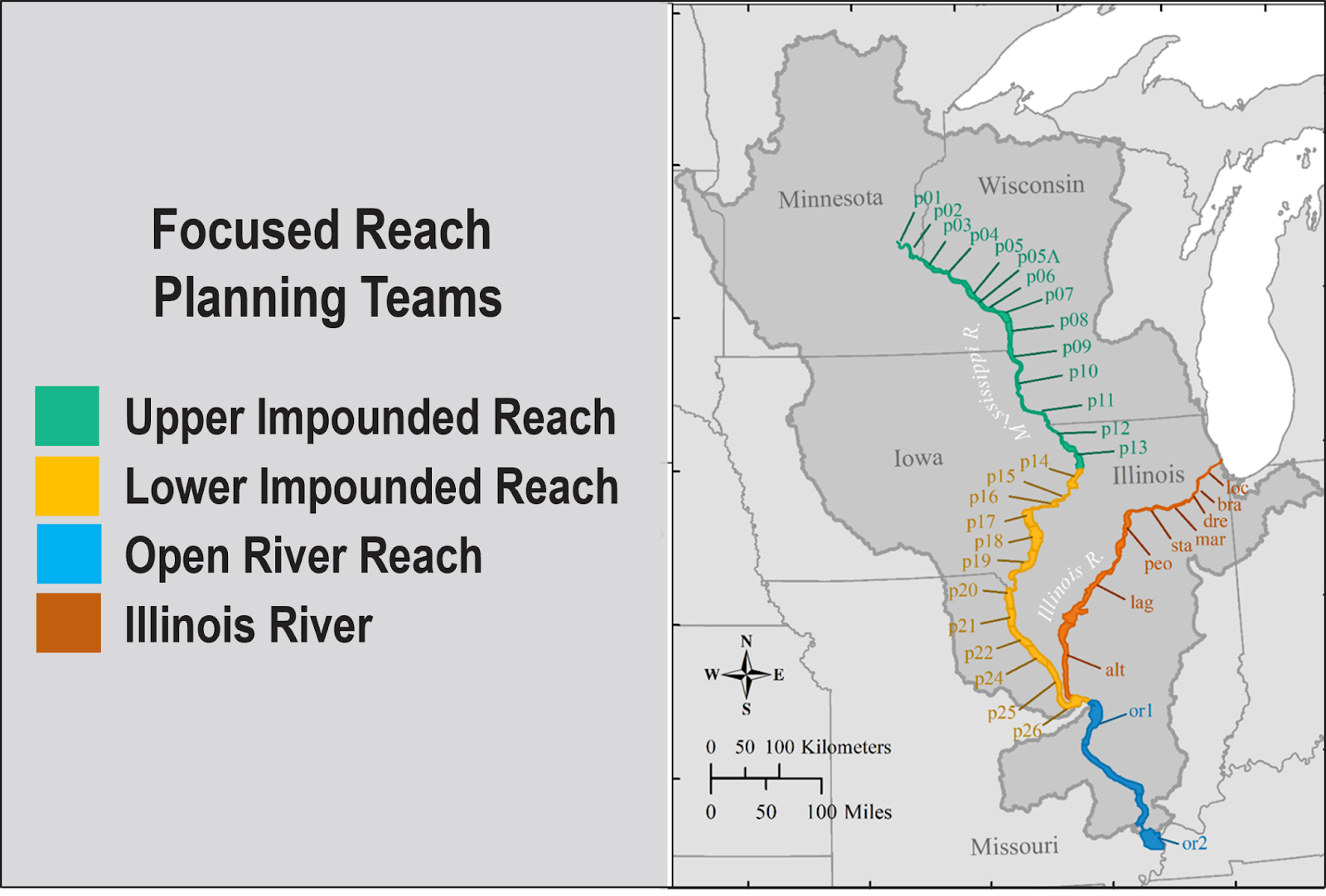

The Corps has used NESP funding to take a big-picture look at sections of the Upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers through a process called Reach Planning to identify restoration priorities, including:

- Emerging ecosystem threats

- Climate change impacts

- Habitat restoration priorities

- Opportunities to reconnect floodplains and restore forests

These plans will guide restoration investments for years to come, shaping how the Rivers adapts to a changing climate.

One Mississippi’s Role: Keeping the River at the Center

One Mississippi is deeply engaged in NESP and Reach Planning to ensure the River’s health remains central to every decision.

Our role includes:

- Watchdogging NESP implementation to ensure ecosystem commitments are real

- Advocating for balanced investments between navigation and restoration

- Elevating climate and biodiversity concerns that are often overlooked in planning

- Identifying floodplain reconnection and reforestation opportunities

- Championing habitat that supports rare, threatened, and endangered species

- Bringing public and partner voices into Corps planning processes

We work to ensure NESP delivers not just efficiency but also resilience.

What’s Next for NESP and What You Can Do

In the coming years, Reach Plans will be finalized, navigation construction will continue, and ecosystem proposals will move forward. Whether NESP fulfills its original promise depends on sustained oversight, transparent planning, and strong public engagement.

Our beloved Mississippi River can be both a working river and a living one—but only if restoration remains a priority.

What you can do:

- Stay informed about NESP and River restoration efforts

- Support policies and decision makers that prioritize ecosystem health alongside infrastructure

- Share this story to help others understand why balance matters

- Join One Mississippi in advocating for a healthier, more resilient Mississippi River by becoming a River Citizen today

The future of the Mighty Mississippi is still being written. NESP is one chapter—but how it unfolds depends on all of us.

Blog by Olivia Dorothy

One Mississippi